Time-Domain Simulation of a Mach–Zehnder Interferometer¶

In this notebook, we design and simulate a passive Mach–Zehnder Interferometer (MZI) in the time domain. This structure contains no active modulation components—all elements are passive, including the spiral delay line used to introduce an optical path length difference between the two arms.

Computes the frequency-domain S‑matrix of each component (using analytical models or full-wave solvers like Tidy3D).

Generates a pole–residue fit for each response to enable efficient time-domain evaluation.

Propagates the input waveforms through the circuit to obtain the output signals.

This workflow requires no manual fitting or convolution code—PhotonForge handles the entire process internally.

[1]:

import numpy as np

import photonforge as pf

import siepic_forge as siepic_pdk

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

07:59:33 -03 WARNING: Using canonical configuration directory at '.config/tidy3d'. Found legacy directory at '~/.tidy3d', which will be ignored. Remove it manually or run 'tidy3d config migrate --delete-legacy' to clean up.

We begin by setting up the default technology, component parameters and frequencies for our MZI simulation.

[2]:

# Set the default technology to SiEPIC OpenEBL

pf.config.default_technology = siepic_pdk.ebeam()

# Define default keyword arguments for all components

pf.config.default_kwargs = {

"radius": 5, # default bend radius in microns

"euler_fraction": 0.5, # fraction of bend length as Euler curve

"port_spec": "TE_1550_500", # default port specification (waveguide type)

}

# Define the optical carrier frequency (around 1550 nm wavelength)

f_c = 193.4e12 # Hz

# Define the electrical modulation frequency

f_m = 10e9 # Hz

Directional Coupler¶

We create a directional coupler using an S-bend geometry with specified coupling distance, length, and offset parameters, designed for 50% coupling efficiency at 1550 nm wavelength. We add an analytical DirectionalCouplerModel for the coupler to enable efficient circuit-level simulations, and a Tidy3DModel for high-accuracy simulations.

[3]:

# Create a parametric S-bend directional coupler

directional_coupler = pf.parametric.s_bend_coupler(

coupling_distance=0.6, # gap between coupling waveguides (µm)

coupling_length=4.7, # length of coupling region (µm)

s_bend_length=5, # length of S-bend transition (µm)

s_bend_offset=1, # lateral offset of S-bend (µm)

model=pf.Tidy3DModel(

port_symmetries=[

("P1", "P0", "P3", "P2"), # reflection across x-axis

("P2", "P3", "P0", "P1"), # reflection across y-axis

("P3", "P2", "P1", "P0"), # inversion symmetry

]

),

)

# Add analytical model for faster circuit simulations, this is the current active model

directional_coupler.add_model(pf.DirectionalCouplerModel(), "Analytical")

# Display the coupler

directional_coupler

[3]:

Then, we define a rectangular spiral with 7 turns, aligned along the y-axis:

[4]:

spiral = pf.parametric.rectangular_spiral(turns=7, align_ports="y")

spiral

[4]:

and a straight waveguide to match the spiral length minus the modulator length.

[5]:

wg = pf.parametric.straight(length=spiral.size()[0])

wg

[5]:

MZI Assembly¶

We now integrate the previously defined components to construct the full MZI. External ports are collected from the two couplers and the modulator’s electrical control port, making it possible to inject optical signals and apply modulation voltage. A CircuitModel is added so that PhotonForge can simulate the device as a network of interconnected subcomponents in the time domain. This completes the layout and connectivity for our MZI, ready for time-domain simulation with optical and

electrical inputs.

[6]:

# Define netlist for assembling the tunable photonic unit

netlist_mzi = {

"name": "MZI",

"instances": {

"dc0": directional_coupler, # input coupler

"spiral": spiral,

"wg": wg,

"dc1": directional_coupler, # output coupler

},

# Explicitly define connections between component ports

"connections": [

(("wg", "P0"), ("dc0", "P2")),

(("dc1", "P0"), ("wg", "P1")),

(("spiral", "P0"), ("dc0", "P3")),

],

# Define external ports of the tunable unit

"ports": [("dc0", "P0"), ("dc0", "P1"), ("dc1", "P2"), ("dc1", "P3")],

# Assign circuit model to the assembled unit

"models": [(pf.CircuitModel(), "Circuit")],

}

# Create a photonic component from the defined netlist

mzi = pf.component_from_netlist(netlist_mzi)

# Visualize the assembled tunable unit

mzi

[6]:

Time-Stepper Initialization¶

One of the key advantages of PhotonForge is how simple it is for the user to set up a time-domain simulation. With just a few lines of code to create a TimeStepper, PhotonForge magically handles all the complexity behind the scenes:

It computes the frequency-domain S‑matrix for each component in the MZI.

It automatically generates a pole–residue fit of these responses.

It prepares the time-domain solver that will propagate the input waveforms through the MZI.

The user only needs to provide:

The desired

time_stepThe optical

carrier_frequencyA frequency sweep range for spectral fitting

Once this is done, the simulation engine is fully initialized and ready to evolve the optical fields through the MZI over time—no manual fitting, no extra setup.

[7]:

# Choose a time step small enough to resolve the modulation period

time_step = 0.001 / f_m

# Create a time-stepper for the MZI with the given simulation parameters

ts = mzi.setup_time_stepper(

time_step=time_step,

carrier_frequency=f_c,

time_stepper_kwargs={

"frequencies": np.linspace(f_c - 200 * f_m, f_c + 200 * f_m, 100)

},

)

07:59:35 -03 Loading simulation from local cache. View cached task using web UI at 'https://tidy3d.simulation.cloud/workbench?taskId=mo-197a9cf2-a04f- 480e-9e69-c0db3ecea223'.

Loading simulation from local cache. View cached task using web UI at 'https://tidy3d.simulation.cloud/workbench?taskId=mo-235c4dc2-0729- 472d-9fad-074bbaf9bd3f'.

Loading simulation from local cache. View cached task using web UI at 'https://tidy3d.simulation.cloud/workbench?taskId=mo-ac08c969-940a- 4b4f-8f73-1bf421c0a062'.

Loading simulation from local cache. View cached task using web UI at 'https://tidy3d.simulation.cloud/workbench?taskId=mo-64f617d7-96e9- 4296-b179-32138270ec9f'.

Progress: 100%

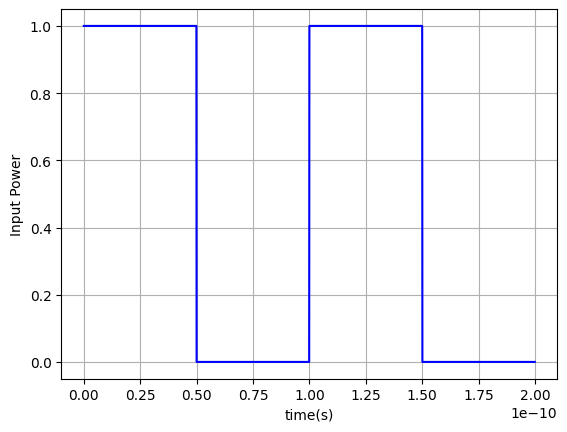

Input Signal Definition

We define the electrical and optical signals that drive the MZI during the time-domain simulation. These inputs will be used by the time-stepper to propagate signals through the MZI.

[8]:

# Simulation grid

N_steps = 2000

t = time_step * np.arange(N_steps)

# RZ digital signal parameters

bit_rate = f_m

bit_period = 1 / bit_rate

duty_cycle = 0.5

pulse_width = duty_cycle * bit_period # high-level duration

# time within each bit

τ = t % bit_period

# Build waveform

rz = np.zeros_like(t)

rz[τ < pulse_width] = 1.0

# Package into TimeSeries

A0_in = np.zeros_like(t)

A1_in = rz

inputs = pf.TimeSeries(

values={

"P0@0": A0_in,

"P1@0": A1_in,

},

time_step=time_step,

)

plt.plot(t, np.abs(A1_in) ** 2, color="blue")

plt.ylabel("Input Power")

plt.xlabel("time(s)")

plt.grid()

plt.show()

Running the Time-Domain Simulation¶

- Resetting the Time-StepperWe call

ts.resetto ensure the simulation starts with a clean internal state, preventing residual values from previous runs. - Executing the SimulationThe

stepmethod of the time-stepper is used to propagate the defined optical and electrical inputs through the MZI over the simulation time, producing the output waveforms.

The resulting outputs object contains the simulated time-domain signals at all output ports of the MZI.

[9]:

# Reset the time-stepper to ensure a clean simulation start

ts.reset()

# Run the simulation for the given input waveforms

outputs = ts.step(inputs)

Progress: 2000/2000

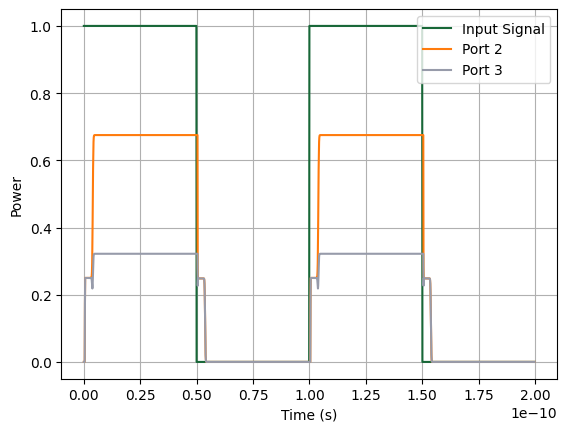

[10]:

# Plot PhotonForge simulation results for both output ports

plt.plot(t, np.abs(A1_in) ** 2, label="Input Signal")

plt.plot(t, np.abs(outputs["P2@0"]) ** 2, label="Port 2")

plt.plot(t, np.abs(outputs["P3@0"]) ** 2, label="Port 3")

# Labels and legend

plt.xlabel("Time (s)")

plt.ylabel("Power")

plt.legend(loc="upper right")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

Interpreting the Time-Domain Output¶

Important: In this example the instantaneous phase difference \(\Delta\phi(t)\) is not exactly \(0\) or \(\pi\), so we do not observe full transmission or perfect extinction. Instead, the outputs settle at partial contrast: \(P_2 \propto 1 + \cos\Delta\phi,\quad P_3 \propto 1 - \cos\Delta\phi,\)

In summary:

Small initial delay → outputs look the same.

Larger spiral-induced delay → interference starts, splitting power between the two output ports, with partial (not complete) constructive/destructive interference.

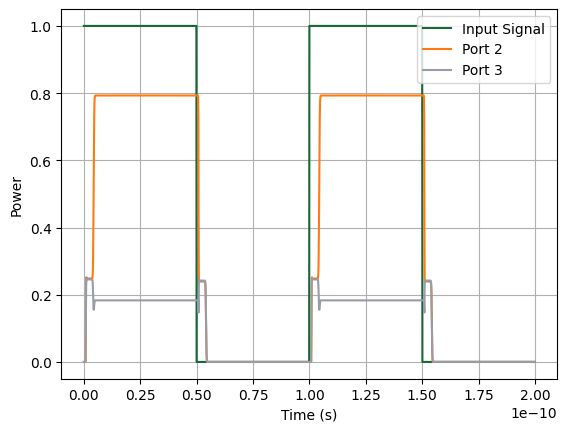

Activating Tidy3D for High-Accuracy Simulation¶

We switch the directional coupler and spiral bends to use their Tidy3D full-wave models, enabling more accurate simulations that capture electromagnetic effects beyond analytical approximations.

[11]:

# Use Tidy3D model for bends inside spiral

spiral.update(bend_kwargs={"model": pf.Tidy3DModel()})

# Use Tidy3D model for directional coupler

directional_coupler.activate_model("Tidy3D")

[11]:

Tidy3DModel(run_time=None, medium=None, symmetry=(0, 0, 0), boundary_spec=None, monitors=(), structures=(), grid_spec=None, shutoff=None, subpixel=None, courant=None, port_symmetries=[('P1', 'P0', 'P3', 'P2'), ('P2', 'P3', 'P0', 'P1'), ('P3', 'P2', 'P1', 'P0')], bounds=((None, None, None), (None, None, None)), source_gap=None, simulation_updates={}, verbose=True)

After activating the high-fidelity models, we re-initialize the MZI’s time-stepper for time-domain simulation. We also reduce rms_error_tolerance to suppress warnings that occur when the pole-residue fit error exceeds this value. While increasing the Tidy3D simulation accuracy would also prevent this warning, the current setting provides sufficient accuracy for the final results.

[12]:

# Setting rms_error_tolerance for pole-residue fit

pf.config.default_time_steppers["*"] = pf.SMatrixTimeStepper(rms_error_tolerance=0.001)

# Set up time stepper

ts_td = mzi.setup_time_stepper(

time_step=time_step,

carrier_frequency=f_c,

time_stepper_kwargs={

"frequencies": np.linspace(f_c - 200 * f_m, f_c + 200 * f_m, 100),

},

)

# Run the simulation for the given input waveforms

outputs_td = ts_td.step(inputs)

Progress: 100%

Progress: 2000/2000

[13]:

plt.plot(t, np.abs(A1_in) ** 2, label="Input Signal")

plt.plot(t, np.abs(outputs_td["P2@0"]) ** 2, label="Port 2")

plt.plot(t, np.abs(outputs_td["P3@0"]) ** 2, label="Port 3")

# Labels and legend

plt.xlabel("Time (s)")

plt.ylabel("Power")

plt.legend(loc="upper right")

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

Why Do the Time-Domain Results Differ Between the Analytic and Tidy3D Models?

These phase changes lead to:

A shift in the interference spectrum of the MZI.

Corresponding changes in the S-matrix at a given frequency (both phase and amplitude can be affected).

A different time-domain output waveform when driven with the same input.